The Perspective | September 18, 2025

The Missing Link in Scaling Sustainable Fashion Innovation

Gauri Sharma

Why Innovation Scaling in Fashion Has an Integration Problem

For the past decade, the fashion industry has pursued innovation in materials, chemicals, and decarbonization with urgency, but one critical factor remains overlooked: supply chain integration.

Brands, funders, startups, manufacturers, and ecosystem partners often operate in silos, despite sharing similar goals. Startups often prioritize partnerships with brands over manufacturers. Brands struggle to make off-take commitments to their manufacturers. Manufacturers are stuck in pilot frenzy, disproportionately bearing financial risk relative to their margins. Funders and VCs sit at a distance from all of this – wondering where to make the most bang for their buck.

True scale is only possible when all four players—startups, brands, funders, and suppliers—work together.

Brands: The Power of the Pull

In fashion, demand signals start upstream. That’s why we begin with brands to convert promising pilots into larger production runs. Here, it’s important to understand the difference between product innovation (like a new material) and production innovation (like a new process). While a new process might offer immediate efficiency gains for a supplier, a new material requires a brand’s commitment to be adopted. But we’re lagging behind as an industry: A report by Fashion for Good states that while 51% of brands have committed to using preferred sustainable materials by 2030, the current global production of next-gen materials is less than 1%.

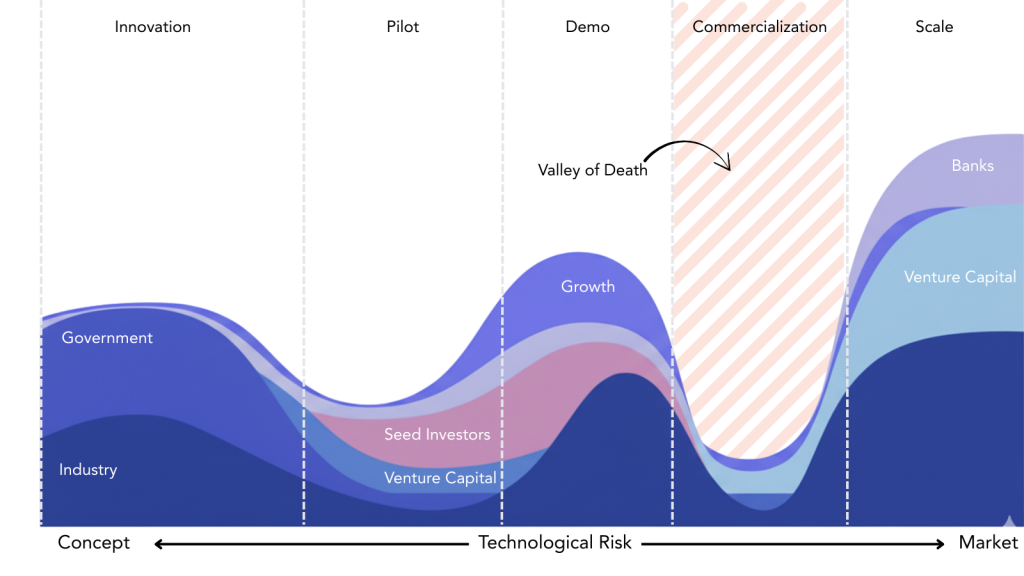

Brands often struggle to “pull” these innovations through long-term offtake agreements due to premium costs or minor quality differences before a startup achieves economies of scale. Brand commitments are crucial in derisking the investment for suppliers and helping innovators survive the “valley of death” — a stage between demo and scaling where innovations sink without the required support. Brand consortia can also play a vital role. For example, Fashion for Good has recently launched two “Fiber Clubs” to generate streamlined demand and provide much-needed orders to mills that have relentlessly tested these materials. This helps prevent pilot fatigue for manufacturers, where different brands conduct similar trials in silos.

Startups: From Brand-First to Supplier-First

For Production Innovation, startups must innovate for the manufacturer, not just the brand. Off-take commitments create predictable demand—but demand only converts if plants can actually run the process. That hand-off is where startups must shift from “brand-first” to “supplier-first.”

A successful pilot doesn’t guarantee a viable integration in a factory setting. In our experience, the startups that successfully scale are the ones that prioritize direct partnerships with suppliers. They get on the ground, in the mills and factories, to run pilots, tweak recipes, and build trust. They’ve focused on making their value proposition to manufacturers operating on razor-thin margins clear: reducing costs or improving efficiencies. For example, we’re currently working with a bio-based prepare-for-dye startup that has honed its technology for its mill partners, showing tangible resource savings in steam, water, and time. It took us 18 months to go from pilot to bulk trials, and we are now working with them to forge a long-term partnership.

Funders and VCs: Accelerating Commercial Feasibility

Even supplier-first startups hit a wall if there are financial constraints. This is where aligned capital can be most effective.

Financial institutions, VCs, and philanthropic funds are vital to scaling. By linking directly with suppliers, they can accelerate commercial feasibility and make better-informed investment decisions. Funders want their portfolio companies to have industry linkages for testing and validation, and suppliers hold the technical expertise.

This collaboration moves a technology from theoretical to practical assessment. For example, we’ve worked with a research institution on a grant-funded study on electrification and decarbonization. We were also able to run a grant-funded pilot for an electrical water recycling technology. This helped us move quickly from a theoretical to a practical assessment of the technology for commercialization.

Suppliers: The Technical Heart of Innovation

Financing and studies can de-risk the idea, but suppliers de-risk the integration.

Suppliers are often seen as passive implementers, but they are the technical heart of innovation. They possess the operational know-how to make a startup’s solution industry-ready. By recognizing their power in innovation integration, suppliers can be proactive partners. They are the most savvy and technically sound stakeholders in the supply chain, and they have the knowledge to mentor and guide startups on the viability and scalability of new solutions.

Across these roles, the pattern is clear: demand signal (brands), an impactful idea that can scale (startups + suppliers), and acceleration capital (funders) locked in a single plan—not a sequence of uncoordinated actions.

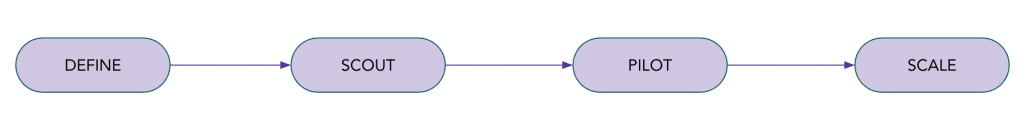

At Shahi, we have developed a four-part process:

This systematic approach allows us to find solutions that directly address our needs, reimagine ideas that aren’t a win-win, and mentor startups to navigate the complexities of a real production environment.

Define: We frame the problem statement based on the requirements of a mill or business unit. For example, our mills are currently looking for technologies beyond biomass to phase out coal.

Scout: We leverage our network of accelerators and partners to identify startups that solve our problems. For example, we collaborated with a corporate innovation accelerator to host a “Pivot with Purpose” deal flow session, where nine energy startups presented their technologies to our teams.

Pilot: We design a pilot plan in a controlled environment with a technical lead. For example, for an electrical water treatment technology, the pilot machine and the startup technician stayed at our facility for 10 days, being closely monitored by our Engineering Head. Together, they determined the efficacy of the solution, tweaking the system as they went along.

Scale: Once a technology clears the pilot and commercial feasibility, it can move into scaling. We recognize that just because something works in a pilot, it may still fail in bulk. If it’s a product innovation, brand pull is needed. For example, we’re currently working with a couple of brand partners to produce bulk orders of a textile-to-textile recycled material.

So what does a new innovation system look like?

If we want to achieve true decarbonization and circularity by 2030, we must move beyond pilots that don’t scale. One-off experiments waste time, while integrated partnerships change systems. That means: brands committing to off-take instead of just targets; startups optimizing for factory floors, not press releases; funders underwriting the uncertain middle, where risks are highest but impact is proven; and suppliers leaning in to this process to make innovations industry-ready.

At Shahi, we’ve built our Define–Scout–Pilot–Scale model to make this kind of integration practical and repeatable. We frame the problem with our mills, bring in the right innovators, and only scale when economics and reliability are clear.

If you’re a brand, startup, or funder ready to co-design the future of sustainable fashion,

* S. Barr, T. Baker, S. Markham, A. Kingon, “Bridging the valley of death: lessons learned from 14 years of commercialization of technology education”, Academy of Management Learning and Education, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 370-388, 2009.

Featured Posts

Featured | December 16, 2025

Shahi Exports Reports Ahead-of-Schedule Sustainability Progress

Featured | October 17, 2025

Shahi Exports Becomes Champion of the Coalition for Reproductive Justice in Business, Partners with UNFPA India

Featured | October 15, 2025

Shahi Introduces ‘The Spark’

Get in touch!

Social Share

Shahi is proudly powered by WordPress